after Multiple delays due to weather and technical issuesSpaceX finally launched a Falcon Heavy rocket Sunday carrying a competitor’s Internet satellite, the first of three next-generation data relay stations capable of terabyte-per-second performance.

After a final hour delay due to gusty winds, SpaceX’s most powerful operational rocket blasted into life at 8:26 pm EDT and lifted off from Kennedy Space Center’s historic Pad 39A with more than 5 million pounds of thrust.

William Harwood/CBS News

Powered by 27 Merlin engines in three strapped-together Falcon 9 first-stage boosters, the Falcon Heavy gained speed rapidly as it consumed its kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants and lost weight. After initially rising straight up, the rocket took off on an easterly trajectory, creating a spectacular early-evening display for area residents and tourists.

SpaceX typically recovers first-stage boosters for refurbishment and reuse, but Sunday needed all available propellant to boost the 13,000-pound ViaSat-3 satellite into its planned orbit.

As a result, three main stages were discarded to fall more than 50 miles into the ocean after the rocket was ejected from the lower atmosphere.

The single engine powering Falcon Heavy’s upper stage shut down eight minutes after launch, placing the vehicle in an initial parking orbit. Two more launches were planned over the next three hours and 44 minutes to get the satellite into a planned geosynchronous orbit 22,300 miles above the equator.

SpaceX

Sunday’s flight capped a busy few days for SpaceX, which on Thursday launched 46 of its low-altitude Starlink Internet satellites from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. The company then launched two medium-altitude broadband satellites for Luxembourg-based SES from the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station on Friday.

All three launches highlight the ongoing race to deploy space-based Internet relay stations to provide broadband access to customers anywhere in the world, including in rural, low-reach or underserved areas, as well as aircraft and ships at sea.

Starlink satellites are part of a rapidly growing constellation of small, low-altitude laser-connected satellites designed, built and operated by SpaceX to provide high-speed, low-latency Internet to users anywhere in the world.

Thousands of Starlinks are needed to ensure that multiple fast-moving satellites are above the user’s horizon at any given moment to provide uninterrupted service. The satellites receive user input and send it to nearby Starlinks for relay to “gateway” ground stations connected to high-speed data lines. Responses are then sent back to the user.

viasat

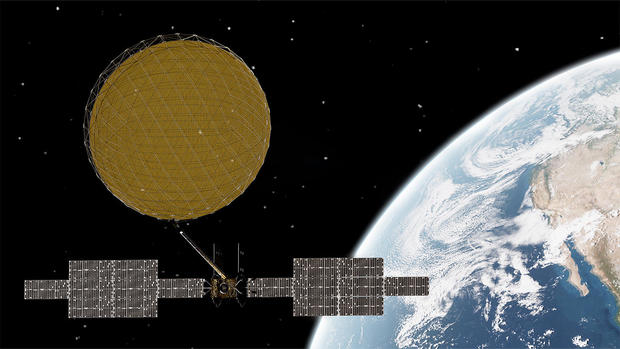

ViaSat is taking a different approach, placing satellites in 22,300-mile-high-orbits above the equator where they rotate in lockstep with the planets below and thus appear stationary in the sky. Three such ViaSat-3 satellites are planned to provide global space-based Internet access on a hemispheric scale.

The powerful satellites are equipped with massive solar panels that generate 25 kilowatts of power and stretch 144 feet when fully deployed.

Capable of handling up to 1 terabyte of data per second, the satellites are equipped with the largest dish antenna ever launched on a commercial satellite. Once on the station, the giant mesh reflector, based on technology developed for the James Webb Space Telescope, will unfold atop an 80- to 90-foot-tall telescoping boom.

If all goes well, the first ViaSat-3 will provide Internet access to consumers in the Western Hemisphere starting this summer. Two more satellites covering Europe, Africa, Asia and the Pacific Ocean are expected to be launched within the next two years.

“If you’re a low-Earth orbit (provider), by definition, to stay in orbit, you’re going to scream across the sky fairly quickly. So your terminal on the ground has to be more complex . . . and more expensive,” said David Ryan, Viasat’s aerospace and commercial director. network president, told CBS News.

“The other advantage of geosynchronous orbit is that you can see a third of the Earth with one satellite. So with one launch, one satellite, you can potentially connect to a third of the Earth. And that’s the principle behind ViaSat-3.”

More William Harwood