New Orleans’ rich culinary landscape includes a restaurant called Saba, which means grandfather in Hebrew. Its owner, Israeli chef Alon Shaya, has won awards for his modern Middle Eastern cuisine, which is ironic given that, when he first emigrated from Israel at the age of four, his roots were something he wanted to erase. “I’ve spent a lot of my life trying to hide my Israeli identity,” Shaya said. eating.”

In culinary school, instead of hummus and pita, Shaya went full Italian; His passions were pasta, charcuterie and pizza. Until, in his mid-30s, on a return to Israel, the dishes of his youth whispered anew. “I realized that I was really missing a part of who I was,” she said. He started cooking Israeli food again. And that, he said, is when he “started to really understand what my identity was as a chef.”

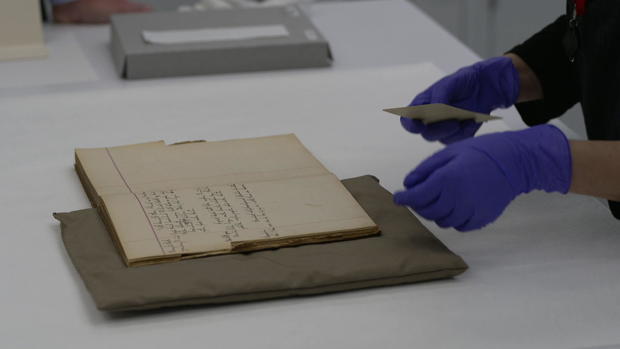

Since then, he has been marinating in Israeli ingredients and their history, which one day brought him to a place perhaps unlikely for a chef: the archives of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. He was both amused and disturbed that during the Holocaust, those forced into Jewish ghettos and concentration camps would write down their family recipes, not to cook, but to remember. “I was amazed at how in one of the scariest moments of someone’s life they could turn to food and that food would have that power,” she said.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Steven Fenves was 13 years old when his train arrived at Auschwitz in 1944. The memory of the food, he said, would remind the inmates of the house: “It reminded you of the joy in this wretched place where you were not human,” he said.

All physical evidence of Fenves’ previous life had been shredded, or so he thought. After she and her sister were freed from Auschwitz, her mother’s recipe book appeared.

CBS News

Steven Fenves’ family lived an upper-middle-class life in the former Yugoslavia. They employed a maid, a chauffeur, a governess and a cook named Maris. “Big lady! Very thick Hungarian accent,” said Steven.

On the day robbers broke into her home while her family was being sent off – presumably to the gas chambers – Maryse, who was not Jewish, ran to save the family’s cookbook for reasons Steven still didn’t fully understand. “I think it was a sense of loyalty, and a sense of love for family,” he said. It was, he admitted, an act of great courage on the part of Maris, when he risked the death penalty.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

When Shaya discovered the book in the basement of the Holocaust Museum’s collection, he had one question: Could he actually talk to someone who remembers eating this food? “And they said, ‘Yeah, maybe we can contact you,'” he said.

When Shaya heard Steven’s story, she was so moved that she started recreating the taste of her childhood.

CBS News

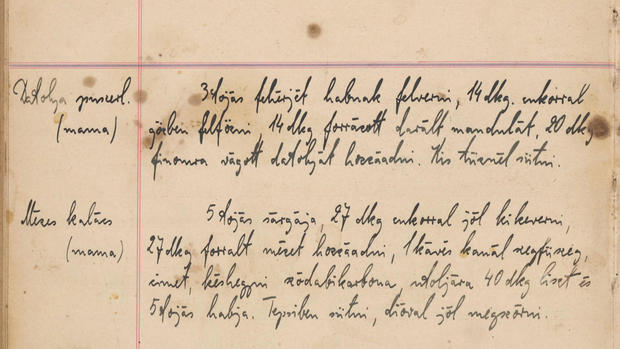

The recipes had to adapt: ”The recipes in this book are not written like recipes like you would see in cookbooks today,” he said.

“So, it’s not like that, half a teaspoon?” asked Cowan.

“No, no. Imagine your grandmother teaching you to make a dish, you know, a bit of this, a bit of that,” Shaya replied.

“Basically, you know, there were no heat setting instructions, because it was all done in a cast iron oven,” says Fenves.

“My oven has no setting!” Shaya laughed.

There were potato circles, a walnut cream cake and semolina sticks.

CBS News

Fenves recipes began to be translated from Hungarian to English, and Shaya began cooking and sending food to Fenves for the first time in more than 70 years.

Steven’s entire family becomes involved, and in the process Fenves regains a painfully personal connection to his story that he says has been lost over the years. “It became such a chore,” he said, while testifying to the horrors of the Holocaust. “I don’t break down in tears at my presentations anymore. It’s so routine, so cold.”

But somehow Shaya’s revival of her mother’s cooking reminds her that all is lost. “Honestly, he brought me out of a big slump in my responsibility to speak as a volunteer survivor,” Fenves said.

“How did he get you out of your slump?” asked Cowan.

“He made it fresh; he made it interesting, and made it moving. … Its influence on me was very clear. I mean, childhood food? It was something touching that went with a lot of other things that went by the wayside.”

Together, these new friends now host donor dinners where her mother’s food is served and Fenves speaks. To date, they have raised more than $300,000 for Holocaust preservation efforts.

Passover is a compulsion to remember both the good and the bad. Alon Shaya offered that gift through food, and because of it, Steven Fenves has a new mission to tell the terrible stories that need to be told.

CBS News

Recipe: Semolina Sticks

For more information:

The story was produced by Sara Kugel. Editor: Ed Givenish.

More

Source link