CAIRO — Economist Riham Shendi began collecting children’s books when she was expecting twins. An Egyptian married to a German and living in New York, she was determined to teach her children her own mother tongue, Arabic. But he finds that it is not as easy a task as many people expect.

Courtesy of Riham Shendi

Arabic, which is spoken in more than two dozen countries, actually functions as two connected but separate language systems.

Arabic is not just a language

“It’s like we speak modern English but write Shakespearean English,” Shandy told CBS News. “It’s a bit further than that – let’s say we speak French but we write in Latin.”

Spoken Arabic (SpA) comes in a wide range of regional dialects. Tunisian, Moroccan and Egyptian Arabic used in everyday life, to name just a few, all have significant differences – to the extent that two speakers from different countries can hardly understand each other.

However, if the same two people are given a transcript of what they are saying in written Arabic (Modern Standard Arabic, or MSA), they should both understand it completely. It provides common ground for literate Arabic speakers across large parts of the world.

Most Arabic books, including children’s books, are written in MSA. But children don’t usually start learning MSA until they’re in school, so reading presents a challenge to them in the early years.

How to teach children to read in Arabic

Many parents, including Shendi, who want to read to their young children, try to translate books in real time for their children, pausing constantly while reading to convert the MSA they just scanned from a page of Arabic into whatever spoken language they use at home. by doing

For young children, jilted delivery is not only confusing, but can be extremely isolating.

“I started by translating on the spot. Then I noticed that when my husband taught our kids German, they would finish his sentences, but not with me,” Shandy recalled to CBS News. “I realized, oh, every time I translate, yes, it’s more or less the same meaning, but I don’t use the same exact words in the same order, and if I’m tired or lazy, I might skip a detail or two.”

Courtesy of Riham Shendi

Dissatisfied with the experience, he sought another solution.

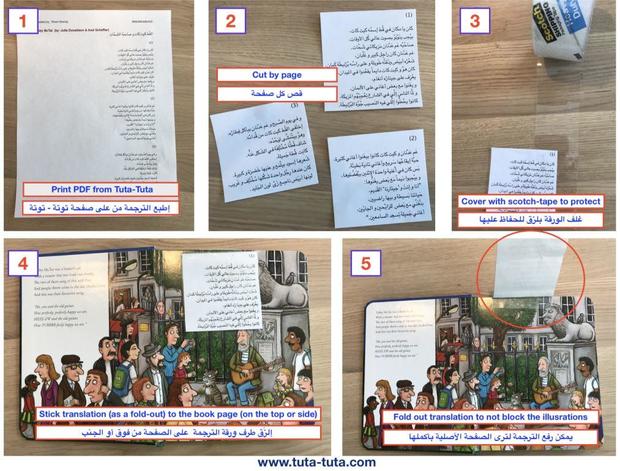

Shandy wrote her translations in SPA, using words she would normally communicate to her children, printed them, and bound them to the book itself.

It “looked terrible,” she admitted. But, “It worked! The kids started finishing my sentences like they do my husband’s.”

So, Shendi set about building her own small library, translating English children’s books into Egyptian spoken Arabic. Then his friends started asking for copies, and then friends of friends.

Finally, he uploaded the translations to his website, along with his “recipe” for creating the text.

Tuta-Tuta/Riham Shendi

When a bestseller isn’t good enough

Shendi offered his translation for free to three of Egypt’s largest publishers, but they all declined the offer, explaining that they did not publish children’s books in Arabic.

For the next 11 months, he went down a rabbit hole to learn about the problem. He wrote an academic paper and his first book “Kan Yama Kan” (“Once Upon a Time”), an Egyptian anthology of international folklore from the public domain, all self-published in SPA.

When Shendy, who has a PhD in applied economics, did the math, he was sure that a good quality book in Arabic, spoken by Egypt’s more than 30 million children, would sell well. He thought publishers would see the success, replicate it, and solve the problems he faced with other Egyptian parents.

The book was a success. It was even a bestseller in Egypt. But Shendy’s economic predictions were off.

“A publisher hasn’t contacted me. Nothing!” So, he did it again. He has published a second edition and two new books. All sold out in less than a year. But still, there was nothing from the publishers. (Watch his meticulous process in his Instagram video below.)

Although the book was a bestseller in Egypt, the bar was quite low: it sold only 1,000 copies per year.

“People would say to me, ‘You’re selling more children’s books than the biggest publishers in Egypt!'” recalls Shendi. “I’d say, ‘True, but we’re both doing so badly!’ When I think that a title reaches only 1,000 children a year, I’m not satisfied.”

Low distribution numbers may help explain why publishers shy away from spoken Arabic. At least the market for printed texts in MSA is significantly larger, as they can sell to schools and individuals throughout the Arabic-speaking world.

Shendy laments that “the tradition of oral storytelling died long ago in Egypt and other Arab countries”, it “has not been replaced by reading books. The idea of sitting down and reading to your child is not something we do.”

“A lot of parents spend money on cake and juice in a shopping mall, but they won’t buy a book for a child. It bothers me, and I think I’m too young to deal with it. I’m a person after all,” he said. He said in frustration. “I’m talking about the upper-middle class who imitate the West in everything. They eat blueberries, quinoa… Why don’t they imitate the West? Why?”

Let go, almost

Shandy couldn’t keep up with the books her children were reading growing up. It doesn’t make sense to translate a novel for your children to read once in your own dialect, especially if they understand English.

“I’m not going to deny my kids all these amazing English books and make them wait six months until I translate a novel,” he said. “I decided to go for content over form! Sadly, I had to drop Arabic as a priority.”

Shendy feels that, in her experiments, she lost both herself and her mother tongue. But he’s not giving up completely.

“I failed compared to my husband, who succeeded in teaching our children to speak and read German only from German bedtime stories,” she said.

Shendy has shifted her focus to trying to help other parents.

“What I do now doesn’t help my own kids, but I do it in hopes that I’m helping another mother down the road to avoid being in the same position,” she said. “No mother should have to go through this.”

Is it better for children to go to school?

The complexities that the many dialects of Arabic present for parents with children’s literature have broader implications for long-term literacy across the Arabic-speaking world.

Without understanding the language in which books are written, it is difficult for children to learn anything else, and this can have a lasting effect.

According to the World Bank’s “Learning Poverty Index,” 59% of children in the Arabic-speaking world, rich and poor, are unable to read and understand an age-appropriate text by age 10. In Egypt, data shows an alarming 69% of children do not fully understand what they are reading.

Shendy noted in a study of Palestinian children that only 20% of the MSA and spoken Arabic vocabulary overlapped, and while 40% of the vocabulary was the same or had the same root (such as “night” in English and “nacht” in German) the other 40% of the words were complete. Different words (think words like “fall” and “autumn” in English).

Is there a solution?

Shendy and others believe that children’s books should be available in spoken Arabic, and that it should even be taught in schools from an early age before students transition to MSA, but some experts reject the argument.

“There’s an elephant in the room that nobody’s paying attention to in Arabic, and that’s the quality, content and methodology,” Hanada Taha, a professor of Arabic language education at Zayed University in the United Arab Emirates, told CBS News. . “We need to come up with engaging content and a fun and kid-friendly approach to bring MSA closer to kids’ daily lives.”

Taha argues that children need to learn MSA anyway “to access the vast body of knowledge written over the last 14 centuries,” that when writing for children it’s best to introduce it earlier, using words common to both MSA and spoken Arabic dialects, and keep it as simple as possible. “To help kids change.”

Exposing children to more SPA, and more formally, may make it harder for them to learn MSA later, Taha said.

“Children have dialects at home. There is no shortage of dialects for a local student in an Arab environment,” he said. “What they really need is exposure to fun and simplified content on MSA.”

His response to people pushing for children’s books in spoken Arabic dialects and blaming the MSA for low literacy rates was simple and clear:

“They publish books in spoken Arabic, there is no ban on writing in spoken Arabic! But how many copies do books written in spoken Arabic sell?”

The debate over the potential merits of publishing and teaching MSA versus spoken Arabic is not new, and there are those who advocate a complete separation between the two, suggesting that one form of the language should be completely abandoned in favor of the other.

That also discourages it.

“This either/or idea I think is very short-sighted. We belong to a language that has two forms and we go in and out of both forms every day,” he said. “We need to educate people, we need to spread awareness, stop fighting about our language, accept what our language is and change our practices and attitudes.”

While using MSA or SPA is sometimes only a market decision, teaching it in schools is, academic debate aside, also a political decision.

Some see the idea of promoting spoken Arabic as an attack on Islam, since the language of the Quran, the Muslim holy book, is the basis of MSA.

Some see spoken Arabic as a distorted form of the language that can never express the richness of MSA. But others see the argument as part of a conspiracy to divide the Arab world.

Meanwhile, many parents are finding that it’s not so easy to just open a book and read to a child.

There is a saying in Arabic that suggests “young children create problems and older ones suffer the consequences.”

In reality, it’s almost always the other way around.

Trending news

Ahmed Shawkat