Pollution updates

Sign up to myFT Daily Digest to be the first to know about Pollution news.

Two years ago, Denis Bukalov mobilised support on social media to block construction of a Chinese-funded water-bottling plant on the shore of Lake Baikal.

Now the environmental activist has set his sights on a political career as he steps up his attempts to protect the world’s oldest, largest and deepest body of fresh water from yet another threat — millions of tonnes of toxic discharge flowing from an abandoned Soviet-era paper mill.

“To be able to debate these things from parliament instead of YouTube or Instagram will bring more government attention to the problems and might actually lead to a resolution,” he said of his political hopes.

That Bukalov’s plan to stand in Russia’s parliamentary election this month were blocked at the last minute — he says without explanation — underlines the scale of the challenge that he and the country’s small band of environmentalists face.

Denis Bukalov (left) with Anton Pirogov, co-founders of the Save Baikal movement, on the shore of the lake in Listvyanka © Nastassia Astrasheuskaya/FT

The 39-year-old is the public face of the movement to save Baikal, a Unesco world heritage site known as “the sacred sea” that contains about a fifth of the world’s fresh water. The lake, famed for its pristine water, faces multiple environmental challenges, from chemical waste to overtourism and the effects of climate change.

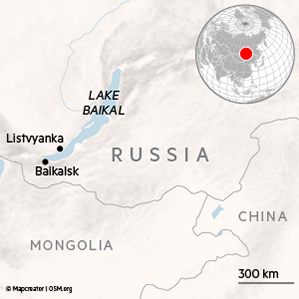

“There’s total indifference to these issues,” Bukalov told the Financial Times from Listvyanka, a tourist town on the west side of the lake, in the Irkutsk region.

Originally from Kazakhstan, Bukalov can recall the day while on a trip to the area that he pledged to dedicate his life to defending the lake. “I sat there watching the stinking discharge flowing into the water and at that moment I promised myself I would protect Baikal,” he explained.

He continued: “Baikal is millions of years old — it came before us and will remain after us. It may be crazy to think of it as a living thing but I consider it alive. It keeps the memory of the universe inside.”

Lake Baikal’s biodiversity, including species unique to its waters such as the world’s only freshwater seal, led Unesco to label it the “Galápagos of Russia”. It was home to one of the “world’s richest and most unusual freshwater faunas, which is of exceptional value to evolutionary science,” the UN agency said.

Vitaly Ryabtsev, a former deputy director of Baikal National Park, said the “flora and fauna has been preserved here since before the ice age”. But he also noted how the water quality had deteriorated in recent years. “There are areas where I used to drink water by simply scooping it up with a cup. Now it’s dangerous not only to drink but even to swim there,” he said.

The most pressing issue stems from the crumbling paper mill in the city of Baikalsk at the lake’s southern tip.

The plant was closed in 2013 under a decree from President Vladimir Putin that called for the formation of a nature reserve at the site.

Locals have seen little progress. The mill is still there along with the constant fear that heavy rains or melting snow will create a mudslide that will wash the estimated 6.5m tonnes of solid and liquid waste still on site into the lake.

Flooding near the plant last year prompted a dire warning from Greenpeace while melting snow sparked another environmental emergency in April.

“If that happens it would be equal to 700 years of pollution by the plant. That would be a tragedy of planetary scope. Even without it, every rainfall releases more waste into the water,” Bukalov said.

A disused paper mill on the southern tip of the lake. Activists fear that more than 6m tonnes of waste still on the site could be washed into Baikal, causing an environmental disaster © Alexei Kushnirenko/TASS via Getty

Rosatom, the state nuclear corporation which late last year became the latest company to take on the clean up, said it hoped to complete the task next year.

“We take our responsibilities to protect Lake Baikal’s unique ecosystem extremely seriously,” it said in a statement. “We understand the significant impact that Baikalsk Paper and Pulp Mill’s legacy issues have had on both the lake’s ecology and local residents and we are absolutely committed to doing everything in our power to rectify this.”

And while Vnesheconombank has unveiled ambitious plans for a Rbs60bn ($820m) luxury hotel complex on the site, Bukalov labelled it a bluff. “We’d welcome a rich investor but clean up the mill and then create a Roza Khutor,” he said, referring to the resort built for the 2014 Winter Olympics.

Besides the threats from chemical waste and climate change, Lake Baikal also has a problem with overtourism, as many people travel there to admire the clear blue ice during the winter months © Natalia Fedosenko/TASS via Reuters

It is not just crumbling Soviet-era industries that threaten Baikal. Scientists say climate change is bringing change at a microscopic level and more visibly in the form of more frequent wildfires that now scar the surrounding taiga forest.

Viktor Kuznetsov, an official with the emergencies ministry, said ordinary people were also to blame for discarding rubbish in and around the lake. “I watch people sitting on the shore eating and instead of cleaning up after themselves they leave their rubbish behind. I don’t know where people’s brains are.”

Corrupt businessmen and incompetent officials add to the problems. After Kuznetsov called for a ban on tree felling around the Svetlaya river that feeds Baikal, the local prosecutor responded by denying the site was in any danger.

“We have the wrong people in power. New people come in and take jobs without any knowledge of the area,” he complained.

Blocked from parliament and short of money, Bukalov said he still planned to stand in local elections next year and continue fight to protect Baikal for future generations.

“Of course we’d like to live better and not have to worry about where to find money for the kids. But I also don’t want to have everything and then sit and watch the lake being destroyed. What will they be left with?”

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here